What if the story we tell about 1990s Seattle is only half true?

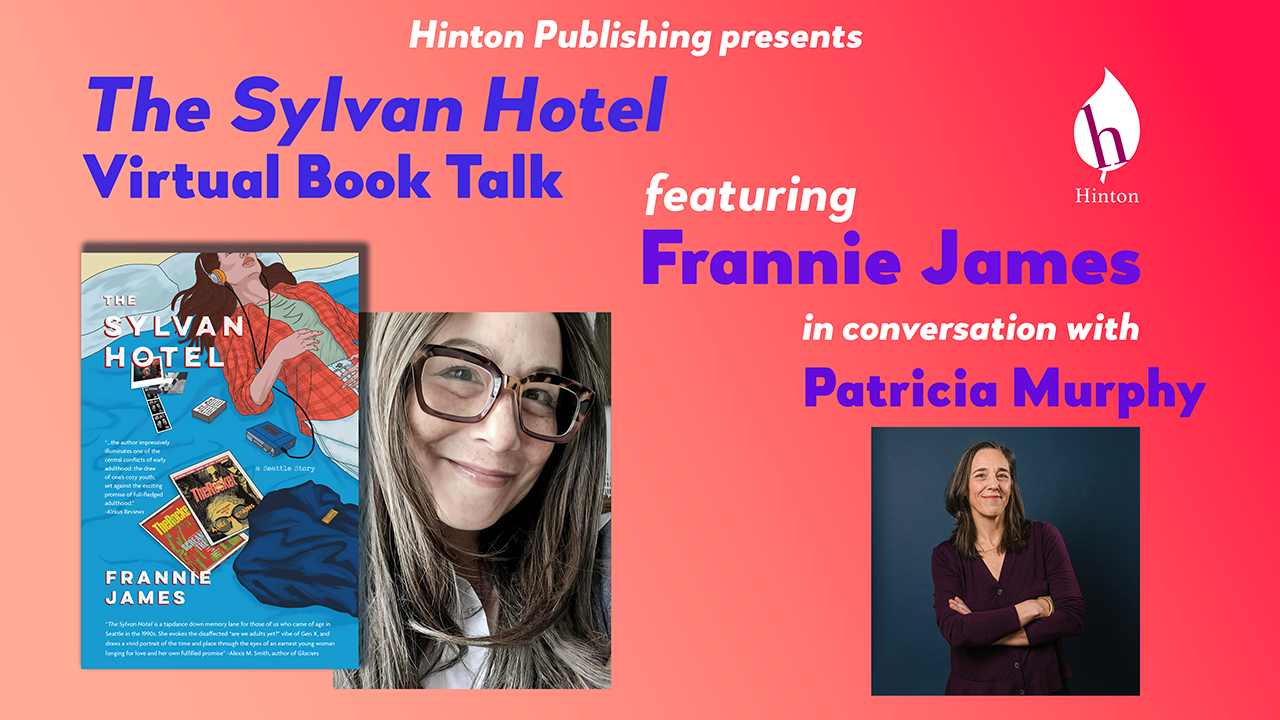

In case you missed it, we were honored to host a wide-ranging conversation with Patricia Murphy, host of KUOW’s Seattle Now, and Frannie James, author of The Sylvan Hotel. Frannie made the case that her debut novel, published by Hinton in October, isn’t really a “grunge novel” at all, even if the era hums through its walls. It’s a coming-of-age story set during Seattle’s most mythologized moment, complete with celebrity check-ins, scene-adjacent cameos, and the inescapable gravity of Kurt Cobain, but its deeper work is widening the frame. If this is Seattle’s most storied era, Frannie argues, it deserves more than one kind of memory: not just bands and excess, but working people, women, mixed-race identities, and the everyday lives that rarely make it into the official archive.

Here are a few takeaways from their conversation to whet your appetite:

At the center of the novel is Joanne, a young woman who describes herself as “accidentally on the inside”—raised in South Seattle, shaped by Catholic schooling and class-crossing proximity, and always acutely aware of who belongs and who is merely tolerated. That awareness runs through everything: who she trusts, where she feels safe, and how often she chooses silence over risk. Frannie spoke about Joanne as a truth-seeker who slowly loses her voice, learning (through family, religion, work, and relationships) that speaking up can cost you love, security, or a sense of place. The novel traces what it takes for Joanne to reclaim agency, not through rescue or revelation, but by learning how to move herself forward.

The Sylvan itself, an old-world boutique hotel perched on Capitol Hill, becomes a pressure cooker for that transformation. The swing shift creates a micro-community that’s both intimate and consuming: after 3–11, the only people awake are the ones you’ve just spent eight hours beside, so coworkers become a kind of found family. That closeness offers real intimacy—not spectacle, but presence, shared time, the quiet relief of being seen, while also threatening to stall lives in place, complicate partnerships, and blur the line between “a job” and “your whole world.” The book refuses to romanticize the workplace, naming the misogyny and harassment embedded in service work alongside the relief and power of having someone who’s got your back.

Running beneath it all is a bittersweet portrait of a Seattle that once felt electric and accessible, a city where working-class people could afford to go out, drift between dive bars and dance floors, and build community without tech or wealth mediating every interaction. Frannie spoke candidly about loving Seattle while grieving it: so much of what the book captures is gone, and the city’s soul can feel buried beneath development. The Sylvan Hotel becomes not just a time capsule, but a memory-keeper, asking what we lose when a city prices out the very range of people who give it life, and what it might mean to protect the places, relationships, and in-between spaces that once made belonging possible.